Oracy education has never just been about elites telling ordinary people how to speak. In this special book extract, Tom F. Wright (Sussex) instead shows how the struggle for articulacy underpinned the struggle for the vote in modern Britain.

The following is an accompanying chapter from Oracy: The Politics of Speech Education (Cambridge University Press, 2024).

Several charges tend to be made by those who are sceptical of the progressive potential of oracy education. One is that it can’t help but be top-down, forcing standardised language upon marginalised people. Another is that oracy is a distraction: by making such a big deal about speaking and listening, we simply avoid more necessary socio-economic changes. Behind this is the claim that oracy schemes are just the latest in a long line of coercive ways of controlling the voices of the powerless. In other words: attempts to "improve” the speaking and listening capacities of ordinary people are oppressive today, just as they always have been.

As someone who studies the history of nineteenth century Britain, I am intrigued by these arguments. I ask myself whether the marginalised people of this period would have recognised their own experience in them. Some undoubtedly would. Many non-elite British people resented what the cultural historian Raymond Williams called “the vulgar insolence” of officials, teachers or other agents of the state telling them that “they do not know how to speak their own language.”[1] Many pushed back against being told how to talk, especially those for whom English was not their primary language.

However, many others may have told us that the above critiques miss the full story. Instead, their experiences remind us that there was in fact another vital tradition at work: one of grassroots oracy education. Throughout the last two centuries, a wide variety of marginalised individuals took a strikingly positive view of speech education. This was particularly true of adult education. Communities opted to prioritise speaking and listening skills through self-learning, discussion groups, public recitations, classes, summer camps and drama clubs. These activities were a familiar feature in cities, towns, and villages across Britain. This world of grassroots oracy education is fascinating for its own sake. But its historical importance lies in the important yet forgotten role it played in progressive social and political movements that helped shape modern Britain.

This chapter presents two examples of this role played by oracy education, both from the long nineteenth century. First, the Chartist campaign for electoral rights for working men during the 1830s-50s. Second, the Suffragist and Suffragette push for votes for women between the 1890s and 1920s. Both movements had far larger social aims in mind than speaking and listening. However, both realised that they needed to maximise their ability to bring about cultural and social change. They saw that creating articulate and discerning communities was key to spreading their message, receiving a hearing, and fomenting the cultural shifts that underpin real political change.

My aim in this chapter is to use these examples to show what a historical perspective on oracy can bring to today’s policy debates. In what follows, I reach back into memoirs, autobiographies, pamphlets, and newspapers to give a broad sense of the role that grassroots oracy education played in the rise of British democracy. It is brief and incomplete, but those who want to learn more can reconstruct the fuller picture from the footnotes.

I have three arguments to make. First, I want to remind us of how much oracy education took place not in schools but through community-driven lifelong learning. In recent decades, historians have revealed how rich the world of grassroots education was in Victorian Britain.[2] However, by underplaying the activities people undertook to improve their oracy, they forget just how central oral communication was to working class and political communities.[3] This tradition can help us re-think adult oracy provision today.

Second, I want to challenge the notion of oracy education as a uniquely top-down project. Seeing non-elites from the past who prioritised transforming their abilities to speak and debate as passive recipients misunderstands their agency. Seeing these working men and women as traitors to a class or a region misses how often what they sought was clarity and clearness rather than a new accent.

Finally, I want to highlight oracy education’s genuine impact on the history of progressive politics. When thinking about political speech in modern Britain, it is easy to focus too much on elite culture: on university debating or parliamentary oratory. But there is another largely forgotten popular educational tradition that needs to be better understood.

Radical Elocution?

If you walk down Bedford Place near the British Museum, you will see a peculiar blue plaque that allows a glimpse of this tradition. It marks the former workplace of John Thelwall (Fig. 1) and lists him as both “political orator” and “elocutionist.” [4] This second label might seem strange. Today, for good reason, ‘elocution’ is a toxic idea, a matter of accent policing and grubby social climbing. But Thelwall was no upholder of the status quo. He was one of the most important enthusiasts for universal rights in 1790s London, whose incendiary speeches (Fig. 2) at open air rallies in favour of the ideas of the French Revolution made him, in the words of Prime Minister William Pitt, the “most dangerous man” in Britain.[5] Repeatedly imprisoned, he was forced to give up his political activities in the early 1800s. From then he channelled his energies into an early form of speech therapy, making the analogy between speech impediments and political “voicelessness,” and promoting elocution as the “enfranchisement of fettered organs.”[6] But what was elocution and why did it appeal to radicals like Thelwall?

Fig 1. John Thelwall’s Blue Plaque, Bedford Place, Bloomsbury, London.

Fig 1. John Thelwall’s Blue Plaque, Bedford Place, Bloomsbury, London.

Fig 2. James Gilray caricature of Thelwall, 1795

Fig 2. James Gilray caricature of Thelwall, 1795

The modern idea began with a group of mostly Irish and Scottish reformers of the mid Eighteenth Century who thought too much attention was being paid to writing and not enough to spoken delivery. In 1756 the Dublin actor Thomas Sheridan published a pamphlet that argued that the low standard and “irregularity” of speech was the “source of the disorders of Great Britain” and that “a revival of the art of speaking” would “cure” the evils of “immorality, ignorance and false taste.”[7] Society would work better, he argued, if its members could all communicate more successfully. He took his ideas on the road, giving lectures across Britain. His crusade was well-received, and he became the most prominent of a group of reformers known as the ‘Elocutionary Movement’ whose ideas generated a genuinely cross-class popular cultural phenomenon that remains, for better or worse, one of the key under-appreciated origin points for oracy education.[8]

With his grand claims for the benefits of better speaking, Sheridan certainly sounds like today’s oracy enthusiasts. But there was obvious difference. One of his paramount aims was to standardise pronunciation across the British Isles. [9] His General Dictionary (1780) offered a system of notation to indicate how words should be expressed, “to put an end to the odious distinctions kept up between subjects of the same king … to all inhabitants of his Majesty’s dominions”[10] In place of “irregularity and disorder” he proposed a “plain and permanent standard of pronunciation” more in line with that of Southern England.[11] The reference to “dominions” was telling. Most elocutionists were from the Celtic fringe but saw a standardized metropolitan accent as patriotically British. For Sheridan, it was “a matter of the utmost importance to the state, and to society”[12] His Scottish counterpart John Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary (1791) argued that improving one’s speaking was “a real service to society.”[13]

With good reason, most modern educators run a mile from this tradition. Sheridan’s influential ideas narrowed the range of spoken English, encouraging ambitious regional youths to shake off local dialects and accents through what some call a form of imperial control.[14] This prescriptive rote learning is the antithesis of how the modern oracy movement sees itself: in the 1960s, Andrew Wilkinson was eager to distinguish his new idea of oracy from what he saw as residue of elocution in the 1922 Newbolt Report and the standardising effects of BBC accents.[15] In the 2010s, charities such as Voice21, have been eager to stress that “oracy is not elocution.”[16]

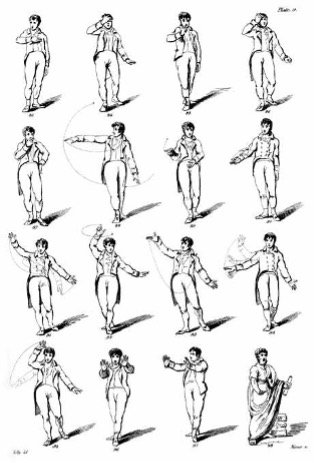

However, there was more to elocution than this. Sheridan and his followers wanted to transform not just pronunciation but the entire style of British oratory. “Would it not contribute to the ease and pleasure of society”, he wondered, “if all gentlemen in public meetings … should be able to express their thought.”[17] In place of stiffness, he wanted a more expressive, emotionally authentic form of delivery, arguing that “to persuade a man into any opinion” you needed “tones of voice …. looks, and gestures, which naturally result from a man who speaks in earnest.”[18] Elocution manuals urged users to think about the effects of their voice and body. As the movement developed, this focus on the body grew, culminating in the kinds of gestures and poses (Fig. 3) in Gilbert Austin’s Chiromania (1806) that strike us as ridiculous today.[19] Some historians have seen this new style of speaking as playing a role in the tone of the era’s politics, for instance teaching the colonists in 1770s Virginia how to literally declare independence from Britain.[20] But as Thelwall’s blue plaque suggests, elocution also played an unexpected role in the history of British radicalism.

Fig.3. Series of elocutionary gestures, Gilbert Austin, Chiromania (1806)

Initially at least, elocution was aimed at those who could afford to attend private schools, public lectures, or buy learning materials. But it soon filtered down the social hierarchy, where it was eagerly embraced in surprising ways. Particularly in the years following the Great Reform Act of 1832, there was a growing interest in how to improve public speaking skills amongst the working class. The ability to speak eloquently in public became, for the first time, relevant to the politicised workingman and prized as an important mechanism for political emancipation. It wasn’t just sharp-elbowed young men who cared about how their voices sounded. Progressives saw that delivery was essential to making a success of their message. We see this in Mary Wollstonecraft’s elocution manual The Female Reader (1789); in the beliefs of leading Chartists such as George Thompson, who had attended Thelwall’s classes; or in the curriculum of dissenting schools such as Joseph Priestley’s Warrington Academy.[21] We can also see it in later manuals such as in the Birmingham socialist and whitesmith George Holyoake’s Rudiments of Public Speaking and Debate (1849), which framed elocution as the democratisation of communication:

weapons innumerable surround them [the workers] of which they have to be taught the use … the scaling-ladders of the wise, which [the upper classes] … have kicked down, are yet of service to those who are below. I have picked up a few of these ladders up and reared them in these pages for the use of those who have yet to rise.[22]

Ordinary men and women realised that elocution amounted to a ready-made toolkit for personal growth that could help their search for social legitimacy – sometimes in causes far away from what Sheridan could have imagined.

Articulate Chartists

One such cause was the electoral reform movement known as Chartism, active from the 1830s to 1850s. Chartists made public speaking central to their promotional activities: mass meetings and rallies, street corner meetings and tavern debates, even heckling and chants at public events, allowed direct oral engagement with communities.[23] (Fig.4) Prominent leaders such as Feargus O'Connor and William Lovett were adept orators, mobilizing the working class to demand political representation. Accounts of all these activities were disseminated through the Chartist and mainstream press. To some in the movement, however, the focus also turned to spreading speaking skills. Though Chartism begun with a strict focus on legislative aims, it soon broadened into an educational culture. This caused a famous split within the movement. O’Connor argued that the priority needed to remain firmly on mass demonstrations and petitions.[24] In ways that prefigure the oracy debates of the 2020s, his wing of the movement suggested that educational aims were a bourgeois distraction from the real ends of reform and revolution. But Lovett and other leaders such as Thomas Cooper maintained that the best route to political reform lay in cultural change and the “political and social improvement of the people.”[25] Quickly derided by its critics as ‘Knowledge Chartism’, this educational idea was as much about how people communicated knowledge as the knowledge itself.

Fig. 4. Chartist Demonstration

Lovett’s pamphlet Chartism: A New Organisation of the People (1840) makes it clear that “political improvement” lay in voices and ears: :

In every country, especially where its institutions are founded on popular power or subject to its control, it becomes the duty of every man to cultivate the abilities God has given him, so that by speaking and writing he may preserve its liberties, by exposing private peculations and public wrong.[26]

Articulacy — or “the art of imparting knowledge to his fellow men” — was a duty of all progressives.[27] Learning was a co-operative venture, and those with education should share what they had gained because “thought will generate thought; each illumined mind will become a centre for the enlightenment of thousands,”[28] Chartists leaders understood that the rank and file needed to be able to share knowledge, explain, and defend arguments effectively. As historian of education Richard Aldrich puts it, the movement relied upon “a cadre of skilled digesters and readers who relayed information in a variety of ways to their less literate colleagues.”[29] One magazine of the movement captured the idealized vision of this process: how on street corners, beside tavern hearths or on factor floors, “a conversation, and sometimes a discussion ensues” between activist and his listeners “and there you ‘behold the man’, firm and erect … with a sonorous and emphatic voice.”[30] Look again at the image in Fig. 4. The point of a scene like this is that the voices of the men conversing in a circle to the right are just as important for the movement as those of the orator on the platform. Oracy was a vital propaganda method, dispersing ideas on a micro scale.

There was also the propaganda value of impressing a wider public. After all, even well-meaning middle-class observers tended to dismiss the communication potential of the working class. The Scottish conservative historian Thomas Carlyle, influentially dismissed Chartists in 1839 as “wild inarticulate souls, unable to speak what is in them.”[31] Charles Dickens too thought the workers unable to adequately explain their positions.[32] Elizabeth Gaskell’s novel Mary Barton (1849) depicted the Chartists as “mute”, and aimed instead to “give some utterance to the agony which, from time to time, convulses this dumb people.”[33] Yet accounts of Chartist speaking often gave the opposite impression. In future Conservative Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli’s novel Sybil (1845), the protagonist is amazed at the “thoughtful speech” of the Chartists labourers me meets.[34] The Christian socialist reformer and novelist Charles Kingsley was “perfectly astonished” at a June 1848 Chartist meeting by the “eloquence, the brilliant, nervous, well-chosen language, the deep simple earnestness, the rightness and moderation of their thoughts. And these are the Chartists, these are the men who are called fools and knaves?”[35] In his novel Alton Locke (1850) he dramatizes the title character as “astonished,” at a Chartist meeting, “to hear men of my own class—and lower still, perhaps some of them—speak with such fluency and eloquence. Such a fund of information—such excellent English—where did they get it all?”[36]

Where did they get it all? For the children and young people of the movement, Chartists set up dedicated schools with a curriculum geared towards reformist ideas.[37] But how was eloquence for adults to be achieved, and maintained? How could the ordinary working woman or man develop as communicators when teaching was so restricted? There were two ways that Chartists saw this happening, through two distinct relationships to oracy.

Solitary Vocal Journeys

The first was largely solitary. In early nineteenth century industrial Britain, in the words of historian E.P. Thompson, “the towns and even the villages hummed with the energy of the autodidact.”[38] By fireside and candlelight, workers taught themselves about science, economics or history through printed materials, including some made explicitly by social movements for their members.[39] They also taught themselves to become better communicators. In the most famous autodidact guide of the century, Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help (1859), learners were reminded that “the orator who pours his flashing thoughts with such apparent ease upon the minds of his hearers achieves his wonderful power only by means of patient and persevering labour”[40] And for many people this labour took the form of a private journey towards eloquence.

This was in part through elocutionary manuals. The cost typically put them beyond the means of most workers --- in 1835, Alexander Bell’s Practical Elocutionist, retailed for 5s 6d, or well over a week’s average wages.[41] But the less affluent often got hold of such materials through lending libraries or mutual associations. What they found was in-depth guidance on all aspects of spoken communication. For example, the socialist Holyoake’s Rudiments presented chapters on “rhetoric”, “delivery”, “questioning” and “repetition.” and urged readers to “acquire mastery over your powers” through “practice so often in private and train himself so perseveringly, that perfection will become a second nature.”[42] These manuals often doubled up as anthologies of speeches so that users could practice their new skills. The most illustrious example of this kind of training took place across the Atlantic in Baltimore in the 1830s, where the African-American activist and orator Frederick Douglass first discovered his passion for rhetoric as an enslaved teenager by coming across a clandestine copy of The Columbian Orator, a collection of speeches he called his “rich treasure” and which he obsessively practised reading aloud to himself.[43] As the memoirs of British working men of the period testify, Douglass was far from alone. Let us consider two examples.

The first is the Newcastle tailor Robert Lowery, who became secretary of the North Shields Political Union and a Chartist lecturer, who recalls practising his speechmaking in the countryside, with livestock as his only audience:

I took a walk into the neighbouring fields in the afternoon until I got to an elevated part of one, where I could see all round, and thus know if any person was approaching within the sound of my voice. I tried to conceive the full tone and manner of speech which I thought it necessary I should deliver, and see how long I could sustain myself without faltering for matter or expression. This I did, and I remember well there was a flock of sheep grazing close by, and they were on the whole perhaps a superior audience … I was satisfied that I could “talk awhile”.[44]

As with many self-learners, the desire to construct sentences aloud, or of articulate key ideas with clarity, is presented almost like a programme of physical exercise. This was just as true for the second example of Thomas Cooper, Leicester shoemaker and Chartist leader who, in the 1820s, dedicated himself to the “forbidden fruit” he discovered in the “tattered and worn Circulating Library” of a local landlord. For Cooper, it was less about oratory and projection, and more about refining one’s expression. He saw it as essential to his development “that I would speak grammatically and pronounce with propriety; and I would do these always,” using the obsessive recitation of literature and poetry to sharpen his ability to express his ideas aloud.[45]

This kind of private, solo learning might seem the antithesis of strong oracy education. We can only develop so far with livestock as our audience. Moreover, there was the danger that these acquisitive, individualist vocal journeys would only take ambitious autodidacts away from their communities. This is in fact exactly what Cooper describes happening:

With my intellectual friends I had conversed in the most refined English I could command; but I had used our plain old Lincolnshire dialect in talking to the neighbours. … that I should sit on the cobbler’s stall, and ‘talk fine’! They could not understand it. To hear a youth in mean clothing sitting at the shoemaker’s stall, pursuing one of the lowliest callings, speak in what seemed to some of them almost a foreign dialect, raised positive anger and scorn in some, amazement in others.[46]

The complex passions that improving one’s speaking skills brings out in others is strikingly captured here --- mixed emotions that he would go on to mobilise in service of the Chartist cause in his speeches as a prominent agitator of the 1840s and 50s. In this way, while there were many autodidacts whose solitary quest for “expression” and code-switching was purely about their own advancement, there were plenty like Cooper and Lowery who saw these skills as part of a larger collective cause. Thankfully, there were also less lonely ways to approach this goal.

Learning Together Through Talk

The twilight world of clubs, discussion groups and debating societies was even more crucial as breeding grounds of grassroots oracy.[47] These were distinct from the equally ubiquitous ‘Mechanics Institutes’ which, despite their name, were mostly run by middle-class reformers and typically greeted with suspicion by Chartists who denounced them as “traps” to “pervert the understanding” of the people.[48] By contrast, Mutual Improvement Societies were founded by and for workingmen. They were the successors of earlier underground debating groups such as Thelwall’s London Corresponding Society in the 1790s, or the Hampden Clubs of the 1810s, that had allowed men of all classes to assemble to freely discuss radical issues.[49] By the 1830s, these societies were less about radicalism per se and more about the ‘improvement’ of the ears, voices, and minds of members. They might involve recitations of literature to exercise the voice and pass on the radical literary tradition. But the most lasting impact on speaking and listening was as spaces for debate. In 1842, the Chartist Dundee Herald framed this purpose as follows:

Every working man should study to acquire sufficient confidence in his own ability to express his opinions freely at all times, and in all places, and before all men. Let debating societies start into existence everywhere ...until every hamlet, village and town in Scotland can produce a Demosthenes and a Cicero.[50]

For Lovett they were “an excellent means for giving confidence to young persons and preparing for public speaking … instructing men in the art of publicly imparting knowledge, instructing their fellows, and defending their rights.”[51] This milieu is notoriously hard to re-enter. Readers of Victorian novels might think of how tavern debating clubs are depicted in Mary Barton (1849) or, looking back from a later decade, George Eliot’s Felix Holt (1866). Modern cinemagoers might have seen this world captured on screen in Mike Leigh’s Peterloo (2017). More instructive are the insights we receive from accounts of participants who talk of their galvanising effect on listening and speaking skills.

The Lancashire weaver Samuel Bamford recalls how Hampden Clubs worked in the 1820s:

Every man would have his half-pint of porter before him; many would be speaking at once, and the hum and confusion would be such as gave an idea of there being more talkers than thinkers — more speakers than listeners. Presently ‘order’ would be called, and comparative silence would ensue; a speaker, stranger or citizen, would be announced with much courtesy and compliment.[52]

By the 1830s, he claims, the clubs “had produced many working men of sufficient talent to become readers, writers, and speakers in the village meetings for parliamentary reform.”[53] This was particularly the case in the capital. Of London tavern discussion clubs of the 1820s, Lovett writes that “It was the first time I had ever heard such impromptu speaking out of the pulpit — my notions then being that such speaking was a kind of inspiration from God … my mind seemed to be awakened to a new mental existence; new feelings, hopes, and aspirations sprang up within me”[54] His contemporary, the anti-slavery leader George Thompson praised the London Mutual Improvement Society as central to his growth --- before learning from how others talked, he said, “I could barely speak a word.”[55]

The fullest sense of what participants gained from these experiences comes from Lowery, who cherished his Newcastle Mutual Improvement Society in the 1830s. Describing it as “a debating club, where the members were allowed to write and read their speeches … or to speak off-hand,” he recalls the incremental process of learning through talk:

I derived much advantage from these discussions; they set up a-thinking and reading on the topics, and accustomed me to try to arrange in consecutive order all the arguments I could think of. This developed constructiveness, and helped to give me a readiness of thought and a greater facility of expression. I remember I was so diffident and deficient in language before that I could not speak a few consecutive sentences extempore; but I gradually got quicker in arranging my ideas, so that, when listening to an adverse argument, I could dot down the answers as the argument went on. I could rise thus to repeat them with more clearness and force… Of the twenty who composed the society one half became public speakers.[56]

As in other accounts, the emphasis is on “clearness and force” rather than refinement of accent. In these structured settings, communities of learners developed skills of listening and how to organise thoughts out loud, whilst also imparting discursive norms of turn-taking, questioning, articulating misgivings in civil fashion. This older generation of radicals invested in institutions that passed on these conventions to the new cadre of activists that emerged from the ashes when Chartism faded in the 1850s.

How much should we make of these examples? The kind of workers who chose to take part and to write about such experiences were necessarily atypical. They likely tell us little about the attitudes towards speaking and listening of the broader mass of the mid-century working class. However, in aggregate, these efforts at grassroots oracy education played an important role in the communications revolution that accompanied the growth of industry, and in the emergence of an increasingly articulate and resourceful working class. These adult education initiatives could never match the kind of training young elite males received in the private schools of the day. But they did amount to a supplementary curriculum in eloquence and critical thinking, and incubators of class solidarity.

We can see the fruits of this in the mid 1860s, when Chancellor of the Exchequer William Gladstone suddenly changed the debate over electoral reform. Voting rights were not to be decided by property alone, he told the Commons in May 1864. Rather, it was to be about the “fitness” of individuals and classes.[57] Crucially, when he made the case for expanding the franchise, he claimed to have been impressed by the “self-improving powers of the working community” in his native Lancashire, and the “painstaking students” of the grassroots libraries, institutes and co-operatives that had helped “to make the working class progressively fitter and fitter for the franchise.”[58] In 1867, The Reform Act spread the vote to larger parts of the urban male working class. Grasroots oracy education of the type discussed above had played its role in proving this “fitness.” It may have been spurred by middle class interventions in working class life, but it was above all a product of the educational culture that emerged from Chartism, one which had an underappreciated vision of elevating voice, dialogue and communication at its heart.

Combating Gender Stereotypes

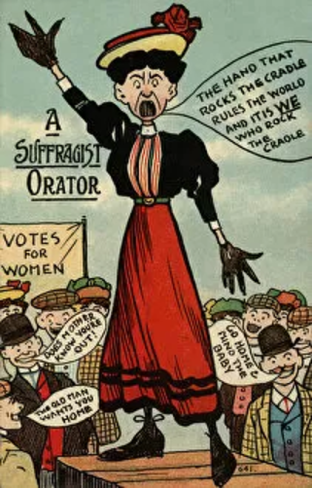

If we jump forward half a century we see a similar dynamic at work in another quite different electoral reform struggle. Women had played a significant part in Chartism and had been frustrated by the side-lining of voting rights for women within the movement.[59] Dedicated spaces for female debate had been created by female Chartists, including the Sheffield Female Political Association.[60] (Fig.5) By 1900 the campaign for votes for women was coming to its mature phase, with a range of rival groups offering competing visions of how its goal might be achieved. The well-known split was between the “Suffragists” of the National Union of Woman Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) and the more radical “Suffragettes” of the Woman’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), formed in 1903 to focus more on civil disobedience and vandalism. The latter’s famous slogan was “deeds not words.” But even they shared the belief that speaking skills of members were crucial: to produce armies of effective campaigners, promote cross-class solidarity, and combat stereotypes about women speakers.[61]

Fig. 5. Cartoon of the Chartist orator Mary Ann Walker, Punch, 5 November, 1842

Fig 6. A Suffragist Orator, 1905.

Oracy skills underpinned all kinds of public activism -- work to which women, especially working class women, were not accustomed, and towards which society was resistant. The difficulties they faced were enormous. Women’s voices were demonised as shrill and hysterical, and public speakers were accused of having renounced their femininity or domestic roles. (Fig 6.). Moreover, since women were often barred from standard speaking venues, they had to adopt unorthodox techniques. Suffragette speaking was often referred to as “skirmishing,” so frequent were attacks on female speakers. Militant WSPU members would heckle speeches by leading politicians such as Winston Churchill or David Lloyd George.[62] Meanwhile, others would use street corners --- work that NUWSS member Hilda Marjory Sharp recalled as the “best possible training in public speaking”:

I would take a chair to a street corner and, mounting it, begin to address empty space, till a small crowd gathered. Or two or three of us might charter a lorry, from which we talked loudly to the workers coming out of the factory gates. If it was an evening job there would always be the pub. There I enjoyed speaking from a stool to a relaxed and bantering knot of people – even though it could only be called entertainment in their eyes.[63]

Both techniques needed high levels of oracy. The militants of the WSPU needed people equipped for confrontational oratory and disruption; the moderates needed the small-scale oracy of gradual interpersonal persuasion.

Talking it Over Across Class Divides

Though far less common than for men, there were a range of notable politically-engaged mutual improvement groups for women. The Edinburgh Ladies Debating Society run by the Scottish suffragist Sarah Mair in the 1860s. In London there was the Langham Place Group and the Kensington Group, all existing to allow women to discuss public affairs and improve their public speaking. On a more national level, the Women’s Co-Operative Guild was founded in 1883 on the lines of earlier male mutual improvement discussion clubs. Deborah Smith, a weaver in one of its Lancashire branches, found inspiration in the “friendly discussions and exchange of opinions” that taught her how, in the words of “my favourite lines from Tennyson,” “tongue could utter/ the thoughts that arise in me!”[64] In 1890s South Wales, religious organisations such as the Wesley Guild offered spaces in which working women developed skills later put to use in politics. Elizabeth Andrews, Rhondda valley miner’s daughter and future Labour Party delegate, describes how the guild enabled her to overcome her initial terror to become a skilled orator and forge a career “training women to take part in public work for the first time.”[65]

As these examples suggest, one feature of the oracy education of the women’s movement was its cross-class nature. Unlike with earlier male-led political movements, women from different walks of life often collaborated, tensely but productively, to establish a common front. As one might expect, the more well-to-do took the initiative. Ladies of leisure in cities set up classes and groups throughout Britain to improve the lives of urban working women.[66] The motivation was quite practical. Though it would be easy, as the upper class suffragette Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence acknowledged of the factory girls she worked with in 1890s Soho, “to become their voice, and to give utterance to their claim upon society,” it was far better for ordinary women to find their own communicative powers: “the battle that is being fought for the workers and will not be won until it is loyally fought by the workers as well.”[67] In 1890, the aristocratic Maude Stanley established the Girls Clubs union to bring together groups that would train young working women in inter-personal self-assurance to enable them to advocate for their rights.[68] In 1914, Sylvia Pankhurst led a breakaway branch of the WSPU, the East London Federation of Suffragettes, which offered training classes at their “Women’s Hall” in Bethnal Green.[69] Sometimes the NUWSS even organised rural boot camps. In the summer of 1912, a mixed-class group of a dozen members travelled to the tiny Conwy Valley village of Tal-Y-Bont to learn banner-making, how to deal with the police and above all, how to control, project and handle their voices.[70]

Fig. 8. Esperance Club girls dancing, c.1900.

The most famous example was the Esperance Club, set up in Camden in 1895 by Pethick-Lawrence and Mary Neal, another upper class suffragette.[71] It was an afterwork club for garment industry workers “to get away from the constant demand on their time and energy”.[72] As it grew, the club drew in a community of female labourers from across the Greater London area, and began to organise rural retreats to Sussex (Fig. 7). The focus was on building solidarity through morris dancing and song. However, smuggled in alongside these entertainments was “a living school for working women” in the form of discussion groups, where girls could increase their knowledge of political questions and, crucially, learn how to talk across class and gender lines. The club hosted weekly debates, including with the nearby St Christopher’s Boys’ Club on Fitzroy Square. Neal’s verdict was that “much sound wisdom has been given from both sides of the table. The girls and boys appreciate this opportunity of discussing together.”[73] One factory girl described the transformative process of simply being invited in as listeners and speakers:

We are glad you men are beginning to talk these things over with us; what is good for a man is good for a woman, I say. It’s not very encouraging for a woman when you men come home from your Trade Union of an evening, and we show a little interest, and ask where you‘ve been to, and you say, ‘You shut up ; that ain’t none of your business !’

By learning to “talk things over” in this way, they were, as Neal put it, “entering into their citizenship” through engagement with the world as listeners and speakers who would be “instrumental in the near future, in altering the conditions of the class they represent.”[74]

“Strengthening Lessons”

Though these activities helped to lay the cultural groundwork, the movement also depended on more focused and practical forms of voice training . Through the nineteenth century, elocution had become an established part of elite private education for young women, and many elocutionists published manuals specifically for female readers.[75] Given the upper-class flavour of much of suffragist activity, it is likely that many activists benefitted from such education. However, many more will have enjoyed dedicated lessons organised by movement leaders. The oracy training on offer within the movement was bodily as well as vocal: these sessions were often called “vocal strengthening” classes, in which activists were issued with guidance on how to behave at meetings and rallies where trouble was anticipated, including keeping one’s temper and engaging hecklers with good humour.[76] As with the Chartists, activists transformed the stultifying repertoire of elocution techniques for unexpected, subversive ends.

Some of this took place in private, elite settings. For example, from 1905 Winifred Mayo gave elocution lessons for WSPU speakers in her Chelsea apartment, while Greta Garnier, a “professor of vocal culture”, offered courses for “strengthening and public speaking” in Mayfair.[77] Other larger classes took place across the capital and in Birmingham. The vocal expertise of actresses was particularly valued, with the Actresses' Franchise League offered training to a range of suffrage societies.[78] The performer Rosa Leo joined the WSPU in 1909 as an ‘Honorary Instructor in Voice Production,” and offered “speakers’ classes” both in her Maida Vale home and in Bethnal Green for the East London Federation of Suffragettes, with only “intending speakers” allowed to attend.[79]

The most famous training of this nature came direct from the Pankhursts. Public adverts for the WPSU in 1905 invited all would-be activists to undergo “a short course of training under one of our chief organisers.”[80] In Manchester, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel toured local women’s groups looking for promising working-class women whose voices they could nurture and develop. Take for example the case of Anna Kenney, who was recruited in 1905 whilst a member of a choir in Oldham, where she was dazzled by Christabel’s persuasive speech in favour of joining the suffragette cause. Her memoir recalls her feeling she “lived on air ... instinctively felt a great change had come'. She began weekly training in speaking on her half-day off from her cotton mill at the Pankhurst’s family home, and found herself giving a speech before a large street-corner crowd in central Manchester:

I found myself at about seven o’clock at night, mounted on a temporary platform, addressing the crowd. What I said I do not remember. I suppose I touched on Labour, the unemployed, children, and finally summed up the whole thing by saying something about Votes for Women. This was my first public speech.[81]

The Pankhursts offered focused training ahead of key rallies and demonstrations. In 1908, Sylvia Pankhurst trained a band of young speakers for the big “Women’s Sunday’ march to Hyde Park on 21 June.[82] These courses could be substantial. The Welsh memoirist and suffragette Helena Gertrude Jones recalls spending “several weeks” in the summer of 1910, “under the watchful and critical eye” of her experienced suffragist mentors, discovering “the power of her own voice and person.”[83] Once trained up, activists then helped share this knowledge of speaking skills. For example, Kenney toured Lancashire pit villages on a mission to nurture other speakers, and found how “every woman there seemed to be a born orator, which shows that if one feels deeply enough one can express one’s thoughts clearly”[84]

What role did this emphasis on oracy ultimately have for the women’s movement? Although the more eye-catching methods of the more militant suffragettes caused the most commotion and remain part of folk memory, the efforts made to boost the communication abilities of the movement ultimately underpinned its success. Oracy helped establish the women’s movement’s deep roots and organisational strength through a patient build-up of organisational strength, and activist campaigning. It enabled the leaders and members of various groups to form alliances, including cross-class affinities and connections. It enabled effective direct engagement with audiences. By speaking confidently and passionately about political issues, suffragettes defied expectations and demonstrated women’s capabilities and leadership qualities. It was essential for campaigning techniques that led to public awareness. Above all, this mutual improvement endeavour challenged educational norms, making women of all classes more aware of and willing to use their voices to protest for social justice, and nurturing the spoken communicative capacities of a half of the population whose resources had been ignored.

Conclusions: What can we learn?

In the debate over speech education today, you sometimes hear the argument made that champions of speaking and listening skills pretend that oracy is a silver bullet. That it will solve all manner of social and educational problems. As far as I can tell, no one is making this claim at all. Oracy education is an essential but not sufficient part of broader social ambitions. In much the same way, I am not claiming that the two social movements discussed above achieved what they did through oracy alone. Both movements realised that speaking well was never going to be enough.

However, they also realised that oracy was indispensable to their aims: that a certain degree of conventional fluency was required to get a hearing; that displays of effective speaking and debate as individuals had propaganda value; and that these skills were ones the status quo didn’t want them to have. Therefore, in hard-headed, pragmatic ways they made grassroots oracy education part of their struggle for democratic ideals, and by doing so pushed British society forward. They were doubtless atypical in their passion for communication. But their experiences represent an important overlooked strand to the intellectual and emotional life of key marginalised groups – a narrative that helps us clarify some assumptions about oracy education held too dogmatically in debates today.

First is the notion that oracy must come from the state. For the overwhelming majority of British people, speaking and listening were skills that had to be acquired piecemeal, furtively and indirectly, through a form of remedial education. As a result, oracy education was often fragmentary, modest, lacking in rigour. And it was doing so against an educational environment that increasingly relegated these skills to the background in favour of the ‘three Rs’, a process that come to a head particularly after the Forster Reforms of the 1870s. Political communities were not the only way in which this took place. There are plenty of other contexts in which voices were nurtured, most obviously through churches, Sunday schools and faith communities of various types. Telling the story of grassroots oracy through the Chartists and Suffragettes instead emphasises its direct role in political history.

Second, is the idea that we must always see oracy education as a top-down imposition. The examples described here tell a different story. Rather than resentment they speak of an eagerness on the part of marginalised groups to increase communicative resources, a hunger for transformation and new vocal role, a desire to be taken seriously and to use new skills to do something about their own exclusion. Oracy was and can still be a transgressive pedagogy.

Finally, they suggest that the best oracy education from the past has always been collective rather than individualistic. These groups of men and women fighting for the vote were motivated not by individual prowess alone but by the desire to use listening and speaking skills to build solidarity and foster the connections necessary for collective action. Members of both movements realised that the kind of democratic future they imagined needed to have communicative equality at its heart. The struggle for articulacy underpinned the struggle for the vote.

[1] Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution (London: Chatto and Windus, 1961)

[2] E P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (London : Pelican, 1968); David Vincent, Literacy and Popular Culture in England 1750-1914 (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1989); Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Class (New Haven : Yale University Press, 2001); Emma Griffin, Bread Winner: An Intimate History of the Victorian Economy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020); James L. Bronstein, The Happiness of the British Working Class (Palo Alto : Stanford University Press, 2023).

[3] Exceptions would be the doctoral work of Janette Lisa Martin, ‘Popular political oratory and itinerant lecturing in Yorkshire and the North East in the age of Chartism, c. 1837-60’, PhD Dissertation, University of York, 2010. For studies of public speaking in the period see Martin Hewitt, 'Aspects of Platform Culture in Nineteenth Century Britain,' Nineteenth-Century Prose 29:1 (Spring 2002), 1–32; For the broader culture of eloquence see Matthew Bevis, The Art of Eloquence: Byron, Dickens, Tennyson, Joyce (Oxford University Press, 2007). Joseph S. Miesel,. Public Speech and the Culture of Public Life in the Age of Gladstone (Columbia University Press, 2001).

ories: John Thelwall and Jacobin Writing (College Park : Penn State University Press, 2001).

[5] Quoted in Rachel Hewitt, A Revolution of Feeling (London : Granta, 2017), p.179.

[6] See Sarah Zimmerman, The Romantic Literary Lecture in Britain (Oxford : Oxford University Press) chapter on ‘John Thelwall’s School of Eloquence’, pp. 60-79; and ‘An Essay Towards a Definition of Animal Vitality’ (1793) in Corinna Wagner, Selected Political Writings of John Thelwall (Oxford : Routledge, 2022), p.10.

[7] Thomas Sheridan, British Education: Or, The Source of the Disorders of Great Britain (Dublin : R. and J. Dodsley, 1756),

[8] For a survey of the elocutionary movement see Linda Mugglestone, Talking Proper: The Rise of Accent as Social Symbol (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1998); Paul Goring, 'The Elocutionary Movement in Britain', in Michael J. MacDonald (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Rhetorical Studies (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017); Brunstrom Conrad. Thomas Sheridan’s Career and Influence : An Actor in Earnest (Bucknell University Press 2011).

[9] Sheridan, Elements of English, v

[10] Sheridan, General Dictionary, 2

[11] Sheridan, General Dictionary, 8

[12] Sheridan, British Education, 160.

[13] John Walker, A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary, (G.G.J. and J. Robinson and T. Cadell, 1791). Their ideas were far from universally accepted. On the other side of the Atlantic, leading lexicographer Noah Webster compared them “tyrants giving orders” to their “vassals”. N.Webster, Dissertations on the English Language (Boston, Mass.,1789), 167-8.

[14] This argument is made in Peter de Bolla, The Discourse of the Sublime: Readings in History, Aesthetics and the Subject (Oxford, 1989); for elocution’s role in accent history see Mugglestone, Talking Proper, x; Sali Tagliamonte, Roots of English : Exploring the History of Dialects (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013)

[15] Andrew Wilkinson, ‘The Concept of Oracy’, English in Education, Volume 2, Issue A2 (June 1965), p.3.

[16] In their 2019 submission to the All Party Parliament on Oracy, Voice 21 stated that “For the avoidance of doubt, it is worth stating that oracy education … is not elocution lessons or limited training on a specific context or aspect of speech” https://voice21.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Voice-21-Submission-to-Oracy-APPG-Final-.pdf

[17] Sheridan, General Dictionary, x

[18] Sheridan General Dictionary, xi

[19] Gilbert Austin, Chiromania: or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (London : Cadell and Davies, 1806).

[20] This claim is made in Jay Fliegelman, Declaring Independence : Jefferson Natural Language & the Culture of Performance (Stanford University Press 1993)

[21] See Ashley Smith , J. W. The Birth of Modern Education , the Contribution of the Dissenting Academies 1660-1800 (Longman : London, 1954); Ian Michael, The Teaching of English : From the Sixteenth Century to 1780 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987); Martin, ‘Popular Political Oratory,’ (2010), p.23.

[22] George Holyoake, Rudiments of Public Speaking (London : Watson, 1849)

[23] For Chartism see Dorothy Thompson, The Dignity of Chartism (London : Verso, 2015); Francis M.L Thompson, The Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain 1830-1900 (Harvard University Press, 1988); Malcolm Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2007). For Chartists ideas about orality see Paul Pickering, ‘Class Without Words: Symbolic Communication in the Chartist Movement’, Past and Present, No 112 (August 1986); 'Songs for the Millions': Chartist Music and Popular Aural Tradition, Labour History Review 74(1):44-63 (April 2009); Owen Ashton, "Orators and Oratory in the Chartist Movement, 1840-1848," in Ashton ed. The Chartist Legacy (London : Merlin Press, 1999).

[24] For this debate see Chase, Chartism: A New History, p.171-178,

[25] Chase, Chartism, p.174.

[26] William Lovett, Chartism: A New Organisation of the People (London : J. Watson, 1840), p.51.

[27] Lovett, Chartism, p.51.

[28] Lovett, Chartism, p.50.

[29] Richard Aldrich, Public or Private Education? Lessons From History (London : Routledge, 2004), p.44.

[30] Vegetarian Advocate, 15 Oct 1848, quoted in Chase, p. 190

[31] Thomas Carlyle, ‘Chartism’ in H D. Traill ed. Critical and Miscellaneous Essays III: The Works of Thomas Carlyle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), p.483.

[32] See Charles Dickens on union leaders in Preston in ‘On Strike’ (1854), The Works of Charles Dicken ( London: Chapman and Hall Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897), p.453.

[33] Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (London : Chapman and Hall, 1848).

[34] Benjamin Disraeli, Sybil, or the Two Nations (London : Colburn, 1845), p. 302.

[35] Charles Kingsley, Diary entry of June 4 1848, quoted in ‘Prefatory Memoir’ in Charles Kingsley, Novels, Volume 1 (London : Macmillan and Co., 1884), xx

[36] Charles Kingsley, Alton Locke, Taylor and Poet: An Autobiography (London : Chapman and Hall, 1850)

[37] For Chartist education see Harold Silver, English Education and the Radicals 1750-1850 (London : Routledge, 2012)

[38] Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, p.146. For nineteenth century autodidact culture see Patrick Joyce, Democratic Subjects : The Self and the Social in Nineteenth Century England (Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 1996), pp.33-45.

[39] Movement of knowledge made my social movements existed, such as Thomas Ballantyne, The Corn Law Repealer’s Hand-book (London, 1841).

[40] Samuel Smiles, Self-Help, with Illustrations of Character, Conduct and Perseverance (London, 1868), 344co

[41] For this figure see adverts in The Edinburgh Review, Vol. 60 (January 1835)

[42] Holyoake, Rudiments, p.42

[43] Frederick Douglass, ‘Life and Times of Frederick Douglass’ (1881), Autobiographies (New York: Library of America, 1994), p.532. See also David W. Blight ed. The Columbian Orator (New York : New York University Press, 1998) xi.

[44] Brian Harrison and Patricia Hollis, Robert Lowery, Radical and Chartist (London : Taylor and Francis, 1979), p.74. It chimes with an image later made famous by Smiles in Self Help of American senator Henry Clay practising speechifying in a farm, “with the horse and the ox for my auditors” Quoted in Smiles, Self-Help, 344

[45] Thomas Cooper, The Life of Cooper, (London : Hodder and Stoughton, 1872), p.56

[46] Cooper, Life of Cooper, p.57

[47] For the culture of mutual improvement societies see Rose, Intellectual Life, pp. 62-70; and John Golby and A. W. Purdue, The civilization of the crowd: popular culture in England 1750-1900 (London, 1984, revised ed., Stroud, 1999), pp. 93-4.

[48] Quoted in Chase, Chartism: A New History, p.144.

[49] For Hampden Clubs see Naomi C. Miller, "Communications: Major John Cartwright and the founding of the Hampden Club". The Historical Journal. XVII, (1974) (3): 615–619

[50] ‘Debating’, [Dundee] Herald, 9 April 1842

[51] Lovett, Chartism, 56

[52] Samuel Bamford, Passages in the Life of a Radical (London : Simpkin, Marshall, 1844), p.6

[53] Bamford, Passages, 7

[54] Lovett, Chartism

[55] See Martin, ‘Popular political oratory’ PhD Dissertation, p. 143.

[56] Brian Howard Harrison and Patricia Hollis eds. Robert Lowery : Radical and Chartist (London: Europa, 1979).

[57] “I venture to say that every man who is not presumably incapacitated by some consideration of personal unfitness or of political danger is morally entitled to come within the pale of the Constitution.” William E. Gladstone, Borough Franchise Bill – Bill 32 House of Commons. Hansard Vol. 175, 11 May 1864. Column 325.

[58] Gladstone, Representation of the People Bill. Hansard Volume 182. 12 April, 1866. Column 1133.

[59] See Jutta Schwarzkopf. Women in the Chartist Movement. (London : Macmillan 1991).

[60] See Rover Constance. Women’s Suffrage and Party Politics in Britain 1866-1914 (London : Routledge, 1967), pp. 4-5

[61] Kathryn Gleadle, Borderline Citizens: Women, Gender and Political Cul- ture in Britain 1815–1867 (Oxford, 2009); Matthew McCormack, Citizenship and Gender in Britain 1688-1928 (Oxford : Routledge, 2019)

[62] Sylvia Pankhurst on the disruption of a 1912 speech by David Lloyd George, quoted in Susan Kingsley Kent, Gender and Power in Britain 1640-1990 (New York : Routledge, 1999).

[63] Quote in Catherine Thackeray, The World of an Insignificant Woman: The Life of Hilda Marjory Sharp (London : Sabrina Press, 2011), p. 79.

[64] Deborah Smith, My Revelation: An Autobiography. How a Working Woman finds God (London, Houghton, 1933), 12.

[65] Elizabeth Andrews quoted in Rose, Intellectual Life, p. 282.

[66] Michael Blanch, ‘Imperialism, nationalism and organized youth’, in J. Clarke et. al. (eds.) Working Class Culture (London: Routledge, 1979),

[67] Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, ‘Working Girls Clubs’ in Will Reason ed.University and Social Settlements (London : Methuen, 1898), p.104.

[68] See ‘Maude Stanley, girls’ clubs and district visiting’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education [www.infed.org/mobi/maude-stanley-girls-clubs-and-district-visiting/. This is a phenomenon depicted in a H.G. Wells novel The Wife of Isaac Harman (1914)

[69] See ‘East London Federation of Suffragettes,’ in Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement, p. 69.

[70] Angela V. John, Our Mothers' Land: Chapters in Welsh Women's History, 1830-1939 (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991), p. 174

[71] See Rachel Holmes, Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel (London : Bloomsbury, 2020), p.183; and Mark Smith, ‘Emmeline Pethick, Mary Neal and the development of work with young women’. the Encyclopedia of Informal Education www.infed.org. <Accessed 2007-05-02>; Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, My Place in a Changing World (London: Victor Gollanz, 1938)

[72]Advertisement for Espérance Club, undated (1905?), Mary Neal Archive, Cecily Sharp House, London.

[73] Pethick, ‘Working Girls Clubs’ in Reason, p.105

[74] Pethick, ‘Working Girls Clubs’, p.105

[75] For the development of this education in the USA see Marian Wilson Kimber, The Elocutionists: Women, Music and the Spoken Word (University of Illinois Press, 2017).

[76] Quoted in Diane Atkinson, Rise Up Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes (London : Bloomsbury, 2003). P.x

[77] See Catherine Wynne, ‘The after Voice of Ellen Terry’, in Katharine Cockin, Ellen Terry, Spheres of Influence (London : Routledge, 2015)

[78] See ‘Actress Franchise League’, in Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (London : Routledge, 1999), p.45; Rebecca Cameron ‘“A somber passion strengthens her voice": The Stage as Public Platform in British Women's Suffrage Drama’, Comparative Drama, 50 (2016), 293-316.

[79] See ‘Rosa Leo’, in Crawford, Women’s Suffrage Movement, p.342.

[80] Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence advert in Votes for Women magazine, 23 February, 1905 quoted in Diane Atkinson, Rise Up Women, p.132.

[81] Annie Kenney, Memories of a Militant (London : Arnold and Co., 1924), p.30.

[82] See Jane Marcus, Suffrage and the Pankhursts (Routledge, 2003), p.9.

[83] Quoted in Krista Cowman, Women of the Right Spirit: Paid Organisers of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), 1904-18 (Manchester University Press : 2007), p. 225.

[84] Kenney, Memories of a Militant, p.134.